How to invest like Benjamin Graham in 2025

A look at the original deep-value grand master and how you can replicate his approach today.

Mr Deep-Value also offers:

Dirt-cheap access to Bloomberg’s No.1 competitor

Separately managed accounts for US clients

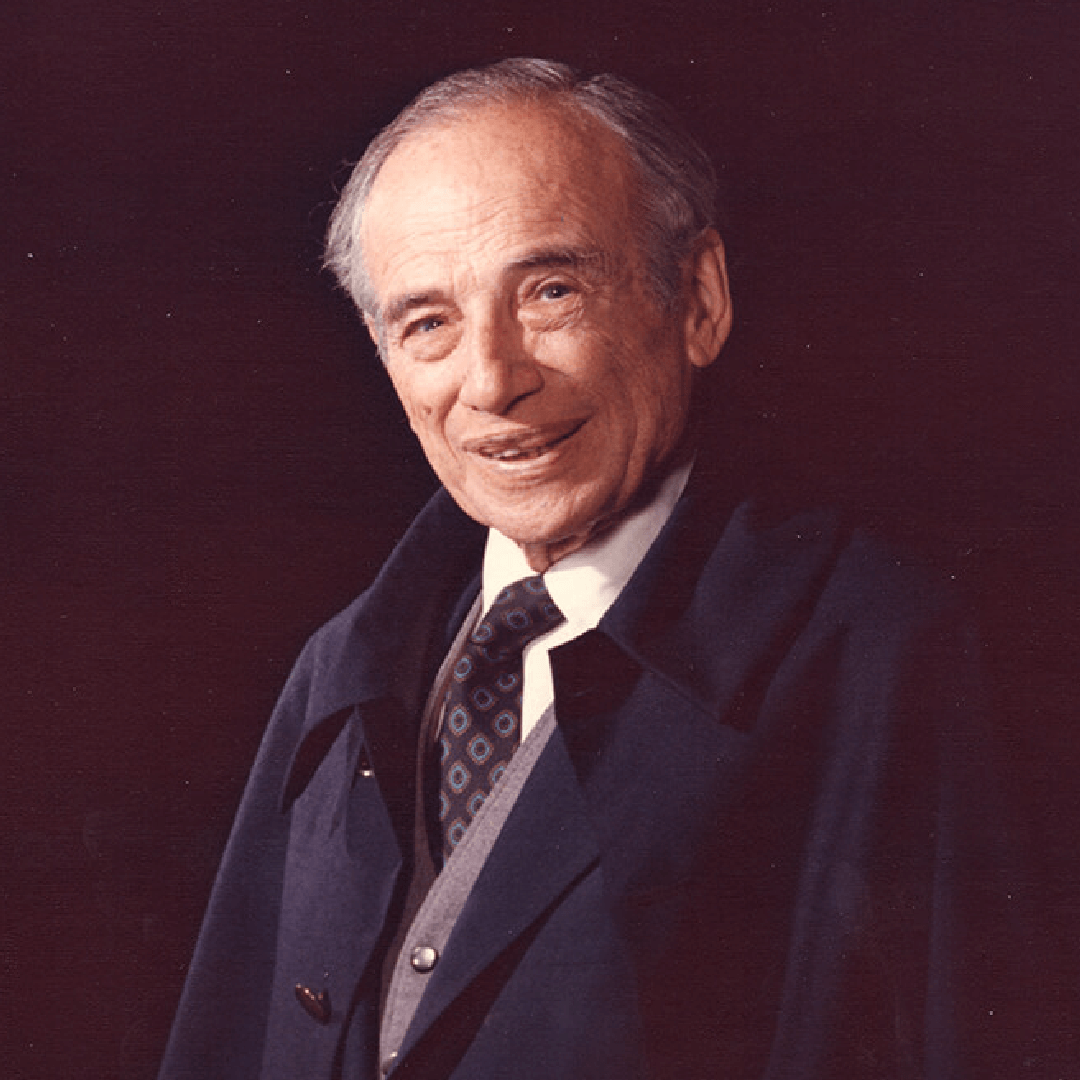

Ben Graham is so central to the concept of deep-value investing that it’s impossible for anyone reading this not to have heard of him.

I actually read the Intelligent Investor long before I realised I was a deep-value investor.

He is the quiet architect behind the whole approach, the teacher who gave Warren Buffett his playbook, and the analyst who showed that buying pounds for pennies can work in real life, not just on paper.

Graham’s ideas were forged in hardship.

Born in 1894, he moved from London to New York as a baby, lost his father young, and watched his family’s fortunes collapse in the Panic of 1907.

That early brush with risk made him fixated on one thing: protecting capital while compounding it sensibly.

After graduating second in his class at Columbia at age 20, he went to Wall Street, then co-authored Security Analysis in 1934 and The Intelligent Investor in 1949, the two texts that underpin modern value investing.

Graham did not rely on clever forecasts.

He relied on arithmetic, audited facts and a concept he made famous: the margin of safety.

If he could buy a business for less than what its tangible assets were worth, he would, and he diversified across many such bargains.

When he found a truly exceptional situation, he acted decisively, as he did with GEICO in 1948 and Northern Pipeline in the 1920s.

He then managed risk with conservative portfolio rules, including a simple stocks/bonds allocation rule and broad (ish) diversification for the cheapest bargains.

This article distils Graham’s method, shows how he actually applied it, and gives you a practical playbook for using it today with modern tools.

His investment strategy

Core principles

1) Margin of safety. Graham looked to buy well below a conservative estimate of value. His purest yardstick was Net Current Asset Value (NCAV): current assets minus all liabilities and preferred stock, divided by shares. He preferred to buy at no more than two-thirds of that figure, ensuring a thick buffer if things went wrong.

2) Facts first. He distinguished investment from speculation by insisting on “thorough analysis,” safety of principal and an adequate return. That definition, from Security Analysis and The Intelligent Investor, remains the north star of value investing.

3) Quantitative filters. Beyond net-nets, Graham outlined sensible checks for the “defensive” investor: long records of dividends, earnings stability, moderate P/E and price-to-book, and a conservative balance sheet. Summaries of those screens typically include 10-year earnings stability, dividends for 20 years, and P/E ceilings of roughly 15 on multi-year average earnings.

4) Mr Market and temperament. Graham’s parable of Mr Market teaches that price volatility is a source of opportunity, not something to fear. You exploit swings by buying when a stock sells below conservative value and trimming or selling when it becomes dear.

What he looked for in the numbers

NCAV bargains (net-nets): Price below 66% of NCAV, often with additional haircuts to inventories or receivables to reflect conservatism. This is the classic Graham “cigar butt” approach.

Strong current ratio and low leverage: For many screens he wanted current assets at least twice current liabilities and total debt comfortably covered by tangible equity.

Earnings stability and dividend record: Ten years of positive earnings and long dividend histories for defensive selections.

Moderate valuation on normal earnings: Examples include P/E based on multi-year (usually 3) average earnings not exceeding 15, and price-to-book at reasonable levels.

How he decided investable vs uninvestable

Investable: Businesses priced below liquidation value or at modest multiples of normal earnings with conservative balance sheets.

Uninvestable: Issues dependent on rosy forecasts, promotional IPOs, or businesses with fragile finances.

Case studies of Graham investments

Northern Pipeline Company (1926–1928): unlocking hidden assets

While studying filings at the Interstate Commerce Commission, Graham found that Northern Pipeline, a Standard Oil spin-off, held a large portfolio of high-grade railroad bonds and securities that was not fully reflected in the price.

The shares traded around 65 dollars, yet the company held roughly 95 dollars per share in liquid securities and paid a healthy dividend.

Graham amassed proxies, pressed for asset sales, and forced a distribution.

Investors ultimately received a 70-dollar cash pay-out and further value, with the total exceeding 100 dollars per share soon after, turning a deep discount into a swift gain.

This was value plus activism decades before “activist investing” became a thing.

GEICO (1948 onward): a once-in-a-generation outlier

In 1948, Graham-Newman bought roughly 50 percent of Government Employees Insurance Company (GEICO) for about $712k.

Regulatory constraints meant the SEC forced a distribution of GEICO shares directly to Graham-Newman shareholders at cost, about $27 a share.

GEICO then compounded for years as a structurally advantaged, low-cost auto insurer.

By 1972, at peak operating levels of that era, one original $27 distributed share had reached a value measured in the five figures, and Graham-Newman’s original stake was worth hundreds of millions.

The investment mixed Graham’s price discipline with an appreciation for exceptional business economics.

Net-current-asset bargains across cycles

Graham documented that buying diversified sets of stocks below working-capital value produced satisfactory results for more than 30 years, excluding the worst of the Great Depression.

He even listed recognisable names that briefly qualified in the 1970 bear market, like National Presto and Parker Pen, showing that such anomalies recur.

(I had a similar experience, which I wrote up here.)

Union Street Railway (via the Graham circle, 1950s)

Although best known as an early Warren Buffett win while at Graham-Newman, Union Street Railway is a textbook Graham net-net:

The shares traded at a deep discount to cash and securities with minimal liabilities.

It illustrates the kind of off-the-map, asset-backed situation Graham trained his analysts to find.

Portfolio management

Position sizing and breadth

Graham separated two worlds:

Defensive investors own a simple basket of high-quality, conservatively valued companies, combined with bonds.

Enterprising investors can pursue special situations and net-nets, but must diversify widely.

For net-net portfolios, Graham recommended roughly 30 positions, which implies roughly 3 percent per holding.

The idea is that any single cheap, distressed small cap can go wrong, but a basket of them can deliver high returns.

When to sell

The popular “sell at 50 percent or after two years” rule is frequently cited, but it is not actually found in Graham’s books.

Graham’s own guidance is more nuanced:

Buy wisely when prices fall and sell wisely when they advance a great deal, while focusing on dividends and operating results rather than price ticks.

In short, sell when the margin of safety is gone.

Stocks and bonds mix

Graham’s most practical risk-control tool is the 25–75 rule.

He advised never holding less than 25 percent or more than 75 percent in equities, with the balance in high-grade bonds.

A 50–50 split works well by default, shifting toward 75 percent equities after declines and toward 25 percent when prices are dangerously high.

This keeps temperament and allocation aligned, not at the mercy of mood.

Long-term record

There is no complete record of Graham’s earliest returns, but we have good data from the Graham-Newman Corporation years.

From 1936 to 1956, the fund earned at least 14.7 percent annually compared with 12.2 percent for the market, after accounting for the realities of the period.

Jason Zweig’s notes in The Intelligent Investor point out that the oft-quoted 20 percent figure likely ignores management fees, making 14.7 percent the more conservative and well-documented estimate.

Graham-Newman closed in 1956.

Regulatory issues around the GEICO position had already forced the distribution of GEICO shares to shareholders in 1948.

The partnership then wound down in an orderly liquidation.

Graham moved to California, taught at UCLA, and spent his later years emphasising the broader, timeless lessons rather than chasing personal fame or assets.

The record matters for two reasons.

First, it shows that a disciplined, conservative method can outpace the market over decades.

Second, it shows that the method is robust across regimes, because most of the returns did not depend on one home-run.

Even so, GEICO demonstrates that Graham could recognise a truly exceptional business when the price was right.

Replicating his approach today

The reason Graham’s playbook still works is simple.

Markets still misprice dull, neglected and distressed businesses, especially at the smaller end of the market where attention is scarce and fear is high.

Accounting is still accounting.

Tangible assets still have liquidation value. Human psychology still swings between euphoria and despair.

Here is a step-by-step plan you can use today, to replicate Graham’s approach:

Step 1: Define your lane

Decide whether you are a defensive or enterprising investor.

Defensive: run a core 50–50 stocks–bonds mix, never under 25 percent or over 75 percent equities, and choose high-quality companies that meet Graham’s basic tests on earnings stability, dividends and moderate valuation. Rebalance when the split drifts by roughly 5 percent.

Enterprising: allocate a sleeve to net-nets and special situations, but respect breadth. Aim for 20-30 net-nets at small weights and keep meticulous notes on balance-sheet quality, catalysts and liquidity.

Step 2: Screen systematically

Use a data source that lets you compute NCAV per share precisely:

NCAV per share = (Current assets − total liabilities − preferred stock) ÷ shares outstanding

Target price below 0.66 × NCAV for your initial universe.

Then filter for basic quality: avoid persistent losses, legal or going-concern flags, and dubious receivables. Expect many micro-caps and illiquid names; spread bets accordingly.

For a defensive screen, apply the Graham attributes:

Positive earnings for 10 years

Long dividend record

Average P/E on 3-year earnings ≤ about 15

Reasonable financial strength, e.g., current ratio around 2 and modest leverage.

Step 3: Verify with primary documents

Graham did his homework at the ICC library. You should do yours in company reports and footnotes.

Confirm working capital, contingent liabilities and any off-balance-sheet items that would reduce NCAV.

He explicitly subtracted preferred stock and recognised off-balance-sheet liabilities in the NCAV arithmetic, so follow suit.

Step 4: Build the basket

For net-nets, build a diversified basket of about 30 names with similar small weights.

You are harvesting a statistical effect, not betting the farm on one story.

Expect a wide distribution of outcomes. A few may double quickly, some may drift, and a handful will disappoint.

The basket is the edge.

Step 5: Set sell disciplines that match Graham’s spirit

Graham’s books do not give a mechanical 50-percent-or-two-years rule, despite the popular meme.

What he does give is a principle: sell when the margin of safety is gone.

For net-nets, that is often when price approaches or exceeds NCAV, or when the thesis breaks because assets disappear or liabilities swell.

For higher-quality defensive holdings, sell when valuation loses discipline or when fundamentals permanently impair earning power.

Step 6: Keep a sensible core allocation

Anchor your overall portfolio in Graham’s 25–75 equity band, defaulting to 50–50.

Let valuation and breadth guide you toward 75 percent equities after big declines and toward 25 percent after serious booms.

This is simple risk control that reduces the odds of emotional mistakes.

Step 7: Use modern tools the Graham way

Graham would have embraced tools that improve measurement while resisting anything that substitutes guesswork for analysis.

Screeners and APIs now compute NCAV in seconds. Use them to find candidates, not to decide.

Document search across PDFs lets you replicate his ICC-library diligence for contingent liabilities and asset details.

Portfolio analytics can enforce sizing, rebalancing bands and basket rules.

News and filings alerts serve as your modern proxy card, flagging corporate actions that can unlock value, like liquidations, spin-offs or asset sales, as they did at Northern Pipeline.

How Graham actually implemented deep value

It helps to see his craft in action.

Buying dollars for 50 pence.

The NCAV rule is exactly that.

Academic tests, most famously Oppenheimer’s 1986 paper, show that baskets of stocks at no more than two-thirds of NCAV delivered returns multiple times the market over 1970–1982, even after reasonable frictions.

This has been backed up by many similar studies, over the years.

Demanding real ballast.

Graham did not hand-wave about earnings stories.

He looked for cash, receivables, inventory and other current assets that could plausibly be realised, then subtracted everything that came ahead of equity.

That is why his method travels well across regimes. It depends on balance-sheet facts.

Knowing when to be very selective.

With GEICO, Graham recognised a superior economic model selling insurance directly to low-risk customers.

He was willing to make a large, one-off commitment at a low price, then let time and growth do the work.

It was value first, quality second, not growth at any price.

Being willing to be an owner.

At Northern Pipeline he acted like a proper owner, pushed management to unlock idle assets and distribute capital, and organised proxies to get it done.

Value investing is not always passive. Sometimes the path from price to value is a decision in a boardroom.

Obviously, most individual investors won’t be in a position to do this but thinking like an owner will prevent poor decisions.

Closing thoughts

Benjamin Graham proved that an ordinary investor, armed with arithmetic, patience and discipline, can earn extraordinary results.

He taught the world to separate price from value, to insist on a margin of safety, and to diversify whenever you are fishing in troubled waters.

His own record over 1936–1956 shows that such a method can outpace the market without needing to predict the future.

You can start the same way today.

Decide your lane. Build a sensible stocks–bonds core. Run a disciplined screen for genuine bargains.

Read the footnotes. Spread your bets. Sell when the margin of safety is gone. Repeat.

The tools are better. Human nature has not changed. That is why Graham’s approach still works.

If you begin now with one position sized sensibly and one small improvement to your process, you will already be investing like Benjamin Graham, not by imitation but by principle.

The method is simple, but patience and discipline is rare. That is your edge (if you can muster it).

Mr Deep-Value also offers:

Dirt-cheap access to Bloomberg’s No.1 competitor

Separately managed accounts for US clients