How to invest like Walter Schloss in 2025

How average investors can beat the market over long periods with simple concepts that have been proven over decades.

Mr Deep-Value also offers:

Dirt-cheap access to Bloomberg’s No.1 competitor

Separately managed accounts for US clients

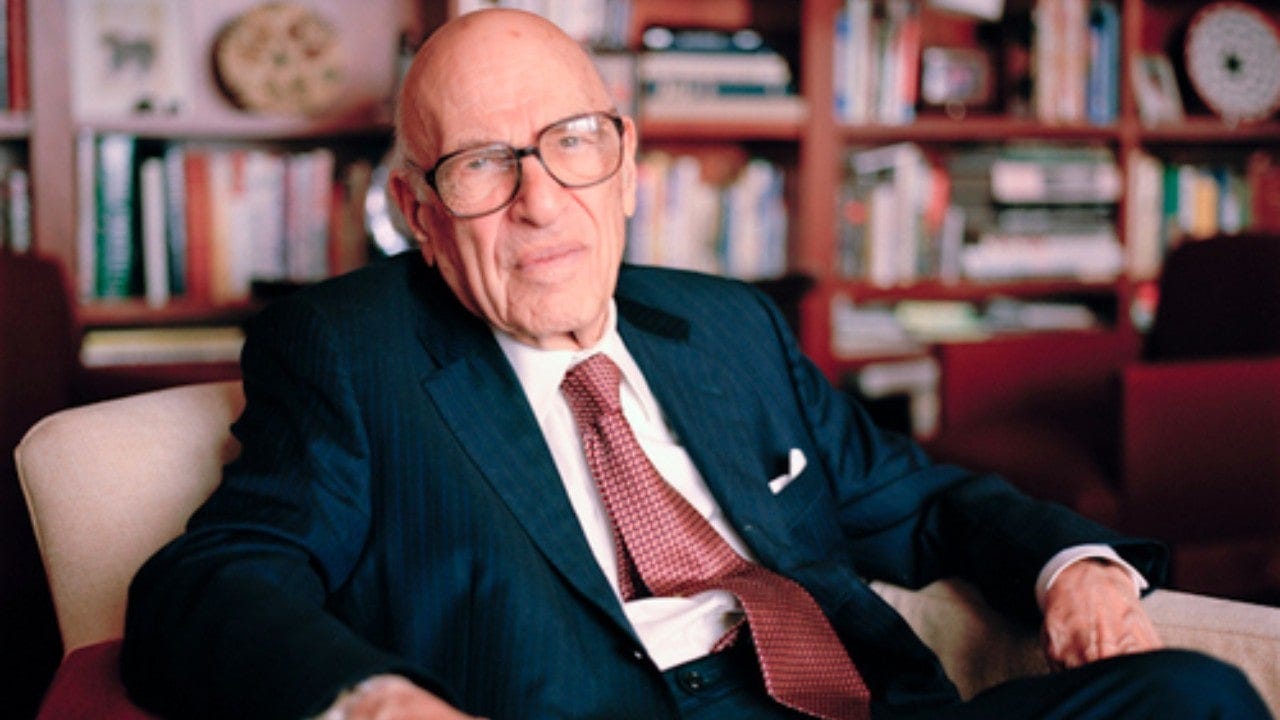

If you want a simple, repeatable way to beat the market without predicting the economy, study Walter J. Schloss.

He started on Wall Street as an 18-year-old runner.

In 1934, he took Ben Graham’s night classes at the New York Stock Exchange Institute, then joined Graham-Newman after serving in the U.S. Army.

In 1955 he set up his own partnership and quietly compounded for nearly half a century, working out of a tiny room inside Tweedy, Browne’s offices.

Warren Buffett later held him up as a rebuke to efficient-market theory: a man with a pencil, Value Line, and extraordinary discipline.

Schloss’s long-term record is legendary.

In Buffett’s 1984 “Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville,” the table shows Walter J. Schloss Associates compounding at about 21.3% before fees from 1956 to 1984, versus roughly 8.4% for the S&P.

Net to limited partners was about 16.1%.

Extending beyond that exhibit, multiple tabulations put the partnership’s four-plus-decade net result at roughly 15 to 16% a year, still far ahead of the index.

Why care today?

Because Schloss invested with a margin of safety, relied on numbers not narratives, and built portfolios that could survive mistakes.

That approach travels well across decades, and is something even the most average investor can replicate with success (imo).

His Investment Strategy

What he looked for

Schloss hunted where prices were lowest relative to hard-asset value.

He started with book value and working capital, preferred little or no long-term debt, liked a long operating record, and scoured the “new lows” lists for stocks hated enough to be cheap.

He summarised his philosophy on one page in 1994.

Here are a few highlights:

“Price is the most important factor to use in relation to value.”

“Use book value as a starting point… be sure that debt does not equal 100% of equity.”

“When buying a stock, I find it helpful to buy near the low of the past few years.”

“Be careful of leverage.”

These maxims came with equally important behavioural rules: have patience, buy and sell on a scale, and keep emotions out of it.

He also kept to his circle of competence.

Schloss famously avoided management meetings, explaining that he was not a good judge of people and that executives are naturally optimistic.

He preferred to “look intensively at the numbers” via Value Line and annual reports.

How he sorted investable from non-investable

In practice, a Schloss deep-value candidate often met several of the following tests:

Low price to book. Sub-1.0 price-to-book was common, and the deeper the discount the better the prospective return, so long as the balance sheet was honest.

Net-net or near net-net. Graham’s NCAV test remained a north star when available: current assets minus all liabilities, purchased at a large discount.

Little debt. He abhorred leverage, especially across cycles.

Long history and preferably dividends. Longevity and cash distributions signalled survivability.

Near 52-week or multi-year lows. Fresh pessimism produced sloppy pricing by the market.

Buffett’s concisely appraised the approach:

“If a business is worth a dollar and you can buy it for 40 cents, something good may happen.”

Case studies in deep value

Boston & Providence Railroad. Schloss described buying the guaranteed stock in the early 1960s for about $96, adding up to roughly $240, in a situation where underlying real estate was the key asset. Portions of the property later sold at figures that more than validated the thesis, illustrating his knack for asset-rich, ignored equities.

Schenley Industries. Around 1960 he bought the liquor company when it traded below working capital. An OID interview recounts his questions about inventory quality and the striking gap between price and liquid resources. It is classic Schloss: buy assets at a discount, wait for normalisation.

A 2007 list of historical holdings, shared with Warren Buffett, shows the kind of names he trafficked in:

Bankrupt railroad securities, coal companies, glove makers, steel, paper and beer companies, even American Express at points when it was unpopular.

The unifying theme is not glamour but tangible value at a discount.

Portfolio management

Schloss managed risk by owning many small bets.

Buffett noted that Walter “has diversified enormously, owning well over 100 stocks.”

Contemporary summaries of Schloss’s process describe a diversified basket of up to 100 positions and a self-imposed cap that no single holding should exceed about 20% of the portfolio.

He weighted more heavily when the discount to value was widest, but he did not run a concentrated, hero-or-zero book.

He averaged in and out.

Buying and selling “on a scale” both cushioned timing error and reduced emotion.

He was patient about exits, often reviewing positions as they approached fair value rather than snatching a quick profit.

His 1994 memo cautions against rushing to sell simply because a share is up 50 percent without re-checking value.

Operationally, he kept overhead microscopic.

Buffett’s letters from 1976 and 1994 joke that Schloss ran a two-man shop from a closet at Tweedy, Browne, with annual office expense that would shame larger firms.

Small size and low costs kept him psychologically and structurally able to fish in illiquid ponds.

Long-term record

Two vantage points tell the story.

Buffett’s 1984 exhibit

In “The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville,” Buffett displayed Walter J. Schloss Associates’ record over roughly 28 years:About 21.3% compound before fees, about 16.1% to limited partners, versus about 8.4% for the S&P over the same span.

That’s decades of quantitative advantage.

The multi-decade arc

Looking across four decades, the Ben Graham Centre’s profile and Schloss’s own tabulations show roughly 15.3% annual net returns from the mid-1950s to around 2000, compared with about 10–11.5% for the S&P.A scanned 1955–1995 table from Walter & Edwin Schloss Associates reports about 15.7% net for the 40-year period to 1995 versus about 10.4% for the S&P Industrials.

Compounding that gap for 40 years is the achievement.

Why is this remarkable?

Because the method is extremely basic.

There is no forecasting wizardry, no leverage, no complex derivatives.

It is the consistent harvesting of mispricings in small, often ugly securities that other investors will not touch.

Replicating his approach today

Why deep value still exists

Schloss’s edge came from behaviour and breadth, not secrets. Those edges still exist because:

Small and micro-cap shares remain under-researched and are often excluded from big funds.

Indexation and factor mandates force selling that ignores asset value.

Humans still extrapolate bad news and over-react to short-term results.

Cheap balance-sheet stocks have shown historical excess returns in multiple studies, including Tweedy, Browne’s review of low price-to-book and net-net strategies.

Academic work continues to find net-current-asset strategies profitable in various markets and periods, though they can be capacity-constrained and lumpy.

That is precisely the sort of inefficiency a small, patient investor can exploit.

A step-by-step playbook

Define your fishing pond

Focus on developed markets where filings are accessible. Screen for market caps under institutional radars and be willing to look abroad when accounting and shareholder protections are acceptable.Run Schloss-style filters

Use any competent screener (we built one here) to find candidates with:

Price to tangible book ≤ 0.8 or, better, ≤ 0.5.

Net-net status when available, or at least a large discount to NCAV, or at least with a positive NCAV.

Debt light balance sheets. Tangible assets are where the value is.

10-year+ operating history and a preference for dividends.

Near 52-week or multi-year lows, indicating capitulation. These inputs mirror checklists widely attributed to Schloss’s process.

Read, do not schmooze

Pull the last ten years of annuals. Rebuild tangible book, working capital, liabilities and off-balance-sheet exposures. Note insider ownership and any dual-class quirks.Construct a basket

Equal-weight 20 to 100 names depending on your opportunity set and temperament. Keep single-name risk capped. Schloss’s general practice was a diversified book with no holding dominating the portfolio too much.Size by discount and resilience

Tilt a little larger when the discount to tangible value is extreme and the debt is trivial. Keep sizes smaller in melting-ice-cube businesses where time is your enemy.Buy and average

Enter on a scale. Many Schloss-style stocks get cheaper after you start buying. Averaging down in a pre-defined range can improve outcomes when value is stable.Hold for value realisation

Set review triggers rather than fixed targets. A common Schloss-like exit is when price approaches TBV or NCAV, or when a corporate action (sale of assets, buy-back, takeover) narrows the gap. His 1994 note warns against reflexively taking a quick 50% without re-estimating value.Rebalance, do not churn

Expect multi-year holds. Trim positions whose discounts have closed. Recycle capital into fresher discounts.Keep overhead tiny

Most of the edge is behavioural, but some comes from low costs. Avoid over-trading. Keep tools simple and focused.

Risk and temperament

Schloss’s style suits investors who are:

Patient and contrarian. You must be comfortable owning what others dislike.

Process-driven. The wins come from many small decisions executed consistently.

Unemotional about quotes. Prices will swing. Value will not move nearly as fast.

Compared with paying high multiples for growth, a balance-sheet-first approach reduces downside through asset coverage and low leverage.

Losses still happen, but the margin of safety tilts the distribution in your favour and makes time your ally.

The method’s chief risks are value traps and structural decline, which you mitigate with diversification, debt aversion, and a willingness to sell when facts change.

Where modern tools help

Schloss did this with paper manuals. Today, you have many more resources available.

Screen globally for low P/B and NCAV discounts in minutes.

Automate watchlists of new 52-week lows that meet balance-sheet criteria.

Pull filings and footnotes quickly to audit asset values.

Track catalysts like buy-backs, liquidations and spin-offs.

But the edge still comes from using the tools to act where others refuse to look.

Putting it together: a working checklist

Here is a concise, Schloss-inspired flow you can reuse:

Balance-sheet bargain

P/B ≤ 0.5, (double check tangible assets)

NCAV discount or positive value present when possible.

Debt light or more cash than debt.

History and behaviour

Ten-year record, preferably dividends.

Multi-year low or recent new low.

Insider ownership or alignment.

Sanity checks

No off-balance-sheet bombs or pension holes that erase the “cheap”.

Industry not structurally outlawed or obsolescent without asset-sale value.

Portfolio fit

Size position so that a total write-off does not dent the portfolio.

Cap single-name exposure, keep many independent bets.

Exit logic

Re-estimate value regularly.

Sell near book or post-catalyst.

Replace with a fresher, cheaper name.

Closing thoughts

Walter Schloss proved that you do not need forecasts, meetings, or charisma to win at investing.

You need a sound yardstick of value, the discipline to buy only with a margin of safety, and the humility to diversify widely and let arithmetic do the work.

In Buffett’s words, he simply bought dollars for forty cents, “over and over and over again.”

That still works if you are willing to go where the bargains are and to wait.

We love the deep-value approach because it’s almost identical to the ‘Moneyball’ approach used in professional sports.

When you let the quantitative statistical data guide you, with patience, it’s much more difficult to lose money then to grow it.

Mr Deep-Value also offers:

Dirt-cheap access to Bloomberg’s No.1 competitor

Separately managed accounts for US clients