A Market-Leading Brand for 4x FCF

A healthy, cash-generative business selling near its liquidation value.

Get a 90% discount off Bloomberg’s No.1 competitor. Learn more here

Introducing today’s stock:

NCAV = 1

TBV = 1

EV / 5Y FCF = 4

P / 5Y FCF = 6

If we use last year’s FCF figure (€10.83M) instead of the 5Y average (€10.53M) the ratios are almost identical.

This is comforting because this business is very cyclical so this shows that the earnings here are fairly ‘stable’, even if a bit lumpy, year to year.

To clarify, the figures needed some adjustments to make them true to my ‘rational private owner’ view.

For example, I had to add back lease payments to the FCF figure and adjust TBV and EV to include all liquid assets, at their realistic values.

Even after the adjustments, as you can see above, it still looks pretty cheap.

One other thing that caught my eye is the brands that this business owns.

They’re not necessarily mainstream-famous, but they enjoy almost total domination within their niche.

This is actually a lot more common than you might think in the world of deep-value stocks.

I wrote up another example I found here and another one here.

This type of set-up is pretty nice because the market usually sells the stock because of uncertainty, rather than any terminal decline.

As soon as the uncertainty clears away, the price recovers and we make money.

Let’s take a look…

The Business

Guillemot Corporation S.A. (GUI) designs, manufactures, and sells interactive entertainment hardware and accessories.

Stuff that people use to play computer games and DJ equipment.

It was founded in France in 1984 and went public in 1998.

It sells its products globally under two core brands: Thrustmaster and Hercules.

Thrustmaster is the larger segment, covering racing wheels, gamepads, joysticks and gaming headsets for PC and console players.

Last year (2024) it generated €113.1M in revenue which was over 90% of total revenues.

Hercules focuses on audio and DJing hardware and software, including DJ controllers, speakers, headphones, DJ software, and more recently stream-audio-controllers.

Last year it brought in €12M, which was almost 10% of total revenues.

Hercules is interesting because they have recently launched a ‘beginner-friendly’ product suite to help wannabe DJs get into the hobby at the ground level.

It’s obviously early days, but it seems like this will grow nicely over time.

Currently it’s only 10% of revenues, and so, isn’t worth worrying about too much.

To calculate the intrinsic value of this business we need to give more consideration to the Thrustmaster brand.

These products include ‘racing wheels’ and joysticks’.

When written like that, they seem a bit old-fashioned. I used a joystick when I played on the NES and Commodore 64.

To help imagine these products better, here’s how the website pitches them:

Much cooler.

The market seems to agree.

In US racing wheels for 2024, the market grew while Thrustmaster held a c.19% share by both volume and value.

In Europe’s five largest markets, the brand ranked number two with 27.6% share by value.

In US joysticks, Thrustmaster was number one with 50.7% share by value and 53.1% by volume in 2024, actually outgrowing the market.

They enjoy licensing relationships with brands such as Ferrari and Gran Turismo.

In September 2024 Thrustmaster signed a strategic sales agreement with JD.com to widen availability in China.

If you’re serious about simulated-engine-sports, it seems Thrustmaster is the kit to have.

What makes these brands so powerful is that once you buy one component, there are lots of other components within the eco-system to keep buying.

Think racing wheels, headsets, gamepads, and pedals among other things.

Guillemot, however, is not a growth story.

It has a stable foothold in the global gaming markets and solid brand recognition and loyalty from its customers.

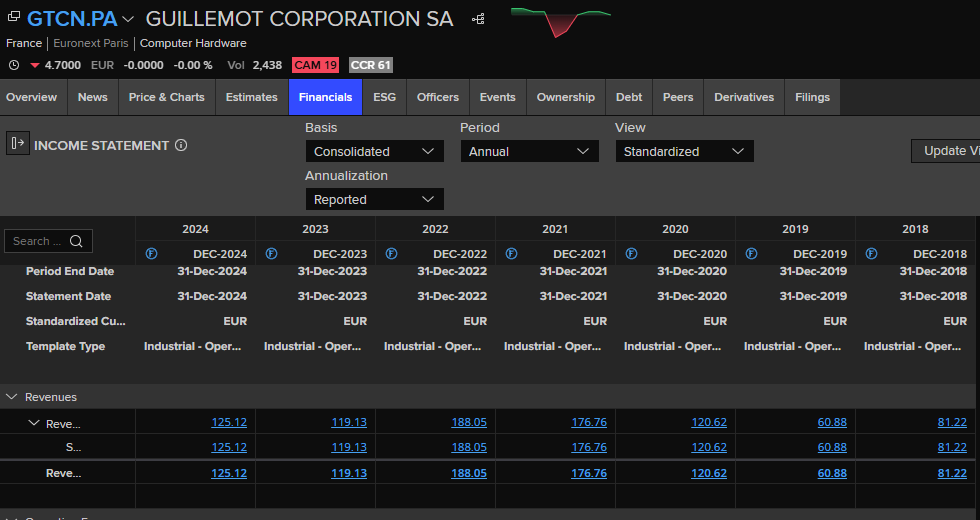

Revenues are pretty stable.

There was the obligatory spike, thanks to COVID, and then the inevitable normalisation of earnings in recent years.

As you can see, current revenues are well off COVID levels but also well above pre-COVID levels.

Management’s stated priorities across the past 5 years have been consistent:

Keep the two brands relevant with regular product refreshes, maintain wide platform compatibility and licensing, manage seasonality and working-capital peaks, and protect the balance sheet.

Boring but simple.

One thing I did find interesting is the CEO’s actions, particularly during the tough year of 2023.

The business failed to meet their KPIs for that year, and he was surprisingly candid about that and about removing any bonuses or salary increases for himself as a result.

Generally, the annual reports, over the years, show a management team that consistently does what they say they will.

When they don’t, they own up and remain transparent.

The business itself is straightforward.

The balance sheet is solid, with current assets almost equally split between invoices, inventory and cash.

Inventories are mostly finished products, which have solid brand recognition. This provides confidence in their sellability.

One thing to note here is that most of the revenues are generated in Q4 of each year (Christmas etc), so inventory tends to build and unwind as the year progresses.

As mentioned earlier, the FCF figure is pretty solid, but we need to remove lease payments to keep it accurate.

Funds from operations are constantly profitable with swings coming in from the working capital component.

Receivables are mostly standard invoices. The company uses an insurance facility to guarantee payment of up to 95% of the value of each invoice.

Interestingly, they don’t apply this to their largest (unnamed) customer.

This is presumably so they can offer that customer better payment terms (that the insurer wouldn’t cover).

Imagine Amazon offered to sell your products through their network, but they wanted 90-day payment terms instead of your standard 30-days.

You’d probably take it, even if you couldn’t insure it, because they’re so big and pose a low risk of non-payment over time.

I think that’s what’s going on here, although the reports don’t go into detail.

The business exited 2024 with solid cash generation and reduced inventory from mid-year levels.

Cash is substantial relative to debt, and is unencumbered.

They also own shares in Ubisoft. These offer added liquid assets to the situation, which I consider liquid enough to include in the EV calculation.

The Ubisoft thing is interesting.

The Guillemot family also founded that and continue to hold a large stake and sit on the board there.

The Ubisoft link has two dimensions:

A family control overlap acknowledged in related-party disclosures, and a financial-asset stake held by Guillemot Corporation itself.

Overall, Guillemot looks, to me, like a cash-generating, cash-rich operation that has been stabilising after a heavy inventory phase, rather than a business in structural decline.

Why It’s Cheap

Guillemot is a relatively small business, in a relatively competitive market.

These types of businesses will never trade at the giddy heights of 20x earnings, like the cool stocks.

Today’s low valuation, though, is clearly irrational, but can be explained by a few factors.

First, 2023 was the inflection year that seemed to reset expectations.

Lower sales, retailer destocking and a gross margin fall drove the steepest leg of the de-rating.

This was the step-down from the COVID era.

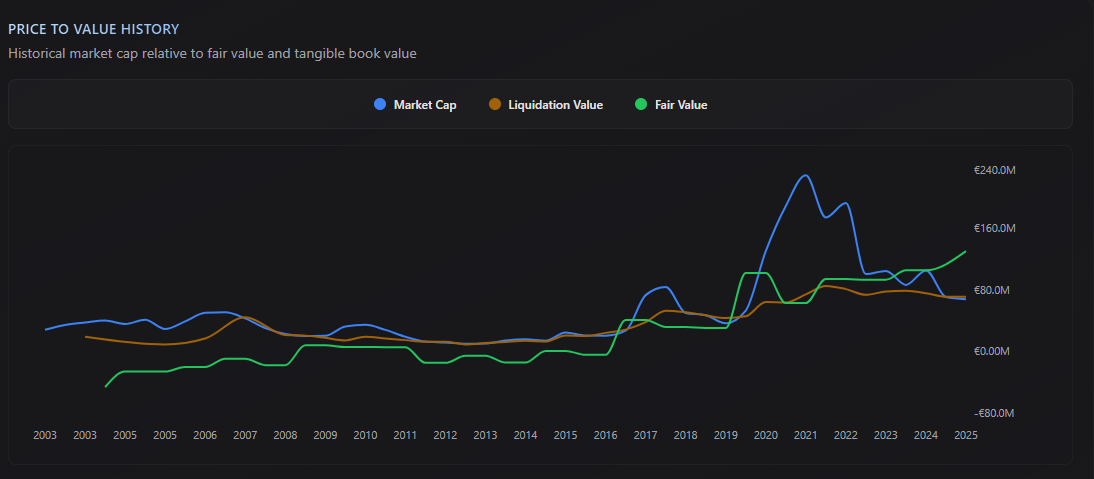

As you can see above, the price of the business has generally traded above its fair value and liquidation values.

The recent drop in price along with the recent increase in value is an interesting situation.

2024 showed operational stabilisation.

Revenue growth of 5% and improved operating income reflected product and title tailwinds, notably in joysticks around a new Flight Simulator product.

The stock price reacted but never really recovered from that 2023 sell off though.

In H1 2025, turnover for the period was softer than expected (-8% YoY), which caused another sell off to the current lows.

In essence, the stock price has followed business performance but has sold off on bad news much harder than it’s risen on good news.

The implied situation in the current price doesn’t match up with the reality of the business, imo.

The Risks

General industry risks are present but less specific.

The accessories market is competitive, with pricing pressure and promotional intensity cited in 2024.

Macro slowdowns or platform transitions can soften demand, and supply-chain costs can re-inflate.

These risks are common to peers and therefore nothing especially concerning to an owner. If you can’t stand these types of risks, you shouldn’t be in business.

There are other things of concern though.

Digging around in the annual reports, I found six risks that are worth noting here.

First, results are strongly seasonal, with about half of yearly sales concentrated between September and December.

That timing creates big swings in inventories, receivables and payables.

Mid-year snapshots can look weak on cash flow and margins, then recover at year-end.

Markets often fixate on the weakest snapshot rather than the full cycle, which can make the business look riskier than it is in reality.

Second, inventories rose during the recent cycle and then slowly normalised.

Large inventories worry investors because of potential obsolescence or discounting.

The filings show the company applies impairments when needed and that stocks fell from the interim peak into the year end, but sentiment can still be fixated in the past.

When investors see big stock levels in a competitive market like gaming, they often assume (unfairly) lower future margins.

Third, reported profit is affected by the mark-to-market movement of the company’s listed stake in Ubisoft.

These fair value changes flow through financial income and can turn a sound operating year into a modest bottom line.

The 2024 reports note a sizable unrealised loss from this stake that reduced net income despite positive operating cash generation.

A private buyer would strip this out when valuing the core operating business, but the market often doesn’t look that closely.

Fourth, management highlights a tough backdrop for gaming accessories.

They note that demand was sluggish and competition intensified in the second half of 2024.

That sort of language puts investors on guard about pricing, promotions and gross margin pressure.

Even when the business is generating cash, a cautious demand outlook can keep the multiple low until several strong quarters rebuilds confidence.

Fifth, customer concentration and foreign exchange add perceived risk.

Receivables are widely insured, which supports cash collection, but a large (unnamed) customer accounted for 34% of 2024 turnover.

This is exacerbated by the fact that 14% of their turnover is unprotected from insurance.

For further context, the top 5 customers accounted for 55% of turnover and the top 10 customers accounted for 70%.

The company also buys a lot in US dollars while much of its revenue is in euros, so swings in exchange rates can squeeze gross margins.

These things pose a risk to revenues, despite the vast majority of invoices being insured up to 95% of their value.

Finally, the ownership structure can create a ‘minority discount.’

The Guillemot family controls 70% of share capital and 83% of the voting rights, thanks to some ‘double-voting’ shares held by some members.

This is stable for operations, and is great as long as the family is focused on execution, cash-generation, and returning capital to shareholders.

However, it does leave us exposed to the risk of a low-ball delisting, if the stock price fell dramatically.

This can turn a 2x-4x opportunity into a small percentage loss, not to mention the opportunity cost.

The Investment Case

The filings depict a cash-rich, founder-controlled company entering a new product cycle with explicit 2025 profit guidance and recent shareholder-friendly actions.

The Group “expects to grow its turnover and deliver a net operating profit in fiscal 2025.”

Today’s market cap seems to imply that the risks will have more impact than the fortress balance sheet and cash-generation of the business.

Trading pretty much at liquidation value assigns virtually no value to the operating business, which is pretty much always profitable.

This feels to me like an irrationally low valuation.

For us to make money here, one of three things (usually) must occur to cause a significant rerating of the stock price.

First, a special dividend or large buyback programme.

This is likely if the cash generation continues.

The Board had authorisation to repurchase up to 10 percent and, on 29 January 2025, retired 400,000 treasury shares purchased in 2024, demonstrating willingness to shrink share count.

They have also paid decent dividends when they can.

The balance sheet and operating business supports this type of catalyst. It would also be in the interests of the owners to increase the value of their holdings in this way.

The next scenario is a buyout of some description.

This is possible but unlikely given the concentrated ownership and industry experience of the Guillemot family.

It would probably take a pretty juicy price to tempt them into a sale, which seems unlikely at this point.

Finally, we have the simplest catalyst of all. A continuation of cash-generation and maybe some mild growth.

At this price, we don’t need growth.

We just need the business to string together a couple of periods of positive business performance, at historically average levels.

Management guides to higher turnover and a net operating profit in 2025, underpinned by the 2025 launch slate, new geographies, and the initial traction of 2024 releases.

It’s also interesting to note that the TTM revenue is sitting at €121M compared to last year’s €125M, with the busiest period yet to be reported.

If you like this idea, my estimate of fair value, if I was buying this company in the real-world, is around €8.50 per share.

Get a 90% discount off Bloomberg’s No.1 competitor. Learn more here