A Net-Net Paying 13% SH Yield for 2x FCF

A cheap stock with an unusually attentive management team...

Get a 90% discount off Bloomberg’s No.1 competitor. Learn more here

Any proper deep-value investor can’t resist a good old cigar-butt.

Sure, we all dream of ‘growth’ and ‘compounders’ but there is something magical about buying a dirt-cheap stock.

The magic is in its simplicity.

No formulas or calculations about the ‘future’.

No concerns about earnings suddenly evaporating thanks to AI.

No worries about an unexpected hiccup in the operating business rearing its ugly head.

The worst case scenario is already priced in.

Today’s business is a classic example of text-book cigar butt.

The current pricing suggests that the business will soon be liquidated, and the assets will realise far less than their book value in the sell-off process.

It suggests that the operating business is completely worthless and won’t generate any profit ever again.

The financial statements and annual reports, however, suggest something quite different.

They show a business that is going through some issues, while holding more cash than the market cap, and still being profitable on a TTM basis.

They also show a management team obsessed with returning capital to shareholders, via cash dividends and aggressively reducing the share count.

The bet is also very simple:

If this business doesn’t die and burn through all its assets in the next 1-3 years, then there is a great chance that the stock re-rates to reflect this reality.

If that happens, we can generate a 50%-100% return on our money.

Let’s take a look…

The Valuation

Shinko Shoji (8141.T) is a Japanese company that deals in electric motors and transformers both in Japan and globally.

We’ll get into the details about what they do shortly, but first, the valuation.

NCAV Ratio = 0.7

TBV Ratio = 0.6

EV/5Y FCF Ratio = 2.5

P/5Y FCF Ratio = 8.4

EV/TTM FCF Ratio = 2.1

P/TTM FCF Ratio = 15

The earnings look pretty lame against market cap, but that’s ok because this whole set-up is about those assets.

The FCF figure is also distorted by a one-off liquidation event in FY25.

That’s why I also shared the TTM-based figures. This provides a more rounded picture of the FCF power of this business.

I’ll explain everything in more detail shortly, but first, let’s take a look at the assets.

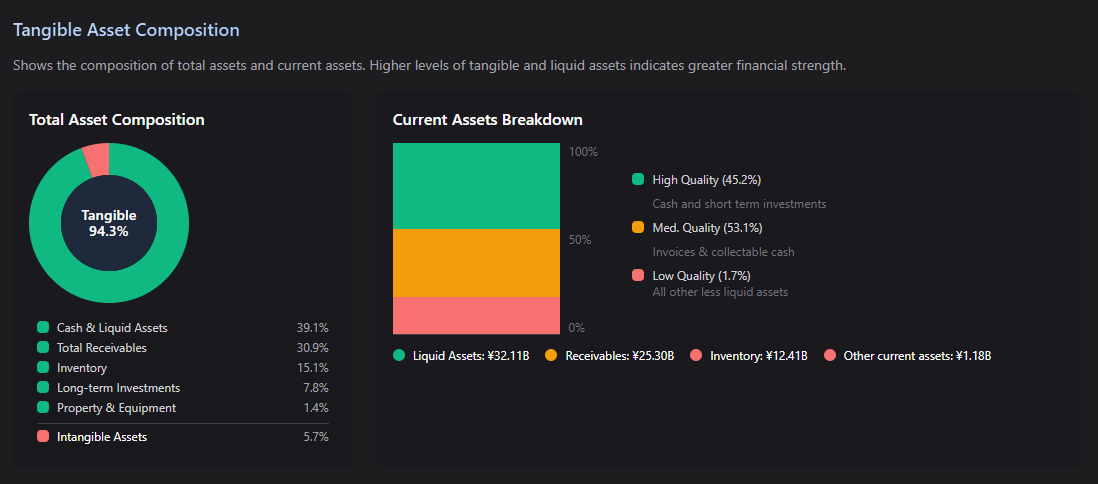

As you can see, almost 40% of the assets are pure cash.

In fact, this increases to 56% when you count liquid assets like non-trade receivables and marketable securities.

The balance sheet is a fortress of liquidity.

Right now, this business is trading at a 25% discount to its NCAV alone, and at only 60% of its TBV.

This is the margin of safety, and the main focus on the set-up.

However, there’s more to this one…

We can’t conduct a valuation without mentioning the shareholder yield.

This is critical because it indicates the tangible returns an investor would make at today’s price.

It’s also important because it gives us an idea about whether or not the market is correct in its assessment of the business.

Remember, the market is implying that the cash and assets are all ‘locked away’ and unobtainable to a minority owner of this business.

In other, a value-trap.

The TTM percentage is 13.6% if we annualise the interim figures.

You’ll notice from this that a lot of the return comes from buying back stock. This is backed up by the share count.

It’s also worth noting that there is no SBC or other forms of dilution happening (now or ever).

So, if we buy the stock today, we have a huge, cash-based, margin of safety in the assets and we generate a strong SH yield while we wait.

The market is effectively betting that the business will waste the cash, but it looks very much like that cash will actually be returned to shareholders, one way or the other.

Not something you see very often in a value-trap scenario.

The Business

Shinko Shoji was founded in 1953, and is based in Tokyo.

They’re an electronics trading company (distributor).

The business generates money by purchasing electronic components, semiconductors, and devices from manufacturers (Suppliers) and selling them to electronics equipment manufacturers (Customers).

This is a classic ‘middle-man’ type business.

They offer three core services, including Logistics and inventory management, assembly services and technical support.

This keeps customers’ supply chains stable, helps them manufacture their products and also offers software development services.

It’s designed as an ‘end to end’ solution.

65.7% of revenues come from selling electronic components, 18.9% comes from software and tech-services while 15.4% is from assembly and manufacturing services.

They serve a variety of different customers.

These include, industrial machinery, automotive, office-automation, and amusement arcades.

They work with some of Japan’s most well-known suppliers, such as TDK, NEC, Kemet and Kyocera.

Although they are headquartered in Japan, they sell globally.

65.9% of sales occur in Japan, 25.7% across Asia as a whole, 8.2% in North America and 0.2% in Europe.

The last five years have been quite eventful for Shinko.

After COVID, global demand for electronics ramped up. Sales went from ¥102B in 2020 to ¥179B in 2023.

Net-income quadrupled during the same period.

This came to a jarring halt when its largest supplier (Renesas Electronics) terminated their contract.

It was a disaster.

Renesas was responsible for over 50% of the company’s revenue at that time.

This turned everything upside down and forced management to come up with a totally new strategy for the business.

Revenues dropped to just ¥116B the following year and net income also fell in line with it.

However, it wasn’t all doom and gloom.

As the contract ended, Shinko liquidated all of the Renesas related inventory and receivables.

This was the main force behind the ‘super-liquidity’ event last year, where changes in working capital brought in over ¥32B for the year.

This provided the business with a glut of cash that now serves as the base for the next phase.

Suddenly, Shinko went from being a stable, growing business to a highly liquid deep-value set up.

This creates a very interesting situation.

A proven management team that is competent in their industry and in allocating capital, given a treasure-chest to redeploy and build the business back up.

The plan they came up with is relatively simple.

First, they aim to replace the lost revenues and then they are specifically targeting the current low stock-price valuation.

The first part of that plan was executed in June 2025 with the acquisition of Shimizu Shintec, a distributor for NEC, with very strong capabilities in facility equipment and construction.

This immediately diversified the revenue base and resulted in a large increase (71%) in the ‘other business’ segment.

This obviously doesn’t fully replace the Renesas revenues just yet, but it does show meaningful progress.

The price they paid for Shimizu was also interesting.

Shinko paid an effective cash price of ¥2.82B to acquire ¥3.27B in tangible net assets.

The deal was immediately accretive to Tangible Book Value by about ¥450M.

Shareholders effectively bought the operating business’s inventory and receivables at a discount.

This is a glimpse into the capital allocation skills of the Shinko management team.

Management has also signed new distribution partnerships with SiMa.ai and Faraday Technology to rebuild the semi-conductor side of things.

Next, they started attacking the fixed-costs.

With smaller revenues (in the short term), things need to be trimmed down. Their ‘early retirement programme’ has reduced employee numbers by 12% already.

This has helped the business remain profitable through the fall in top line revenues.

Finally, they are also focused specifically on the stock price.

In the reports, management specifically states they are trying to get the stock price above book value.

They’re doing this the old fashioned way. Aggressive buybacks, while the stock is cheap, and dividends.

They changed their pay-out ratio policy to 50%.

These actions alone provide over 60% upside from today’s price.

This is all neatly explained as part of the new ‘medium-term’ plan (Japanese companies love these).

It was launched in October 2024, and sets the following specific targets for March 2028:

Total revenues to return to ¥170B per year.

Net-Income from those revenues will return to ¥4.5B per year.

A Return-on-Equity of 8% or more per year.

This also implies that FCF will return to pre-crisis levels of roughly ¥2B - ¥4B per year.

The current market cap is just ¥30.69B.

Management has successfully navigated the ‘liquidation phase’ without bleeding cash.

In fact, they successfully monetised the working capital into a massive cash pile.

They have also successfully rightsized the workforce.

The remaining challenge is the ‘growth phase’ and proving they can reinvest that cash to hit the ¥170 billion sales target by 2028.

But, it’s worth repeating that we don’t need any of that growth to actually happen in order to get a stock-price re-rating.

We simply need the market to accept that management won’t just burn through all the assets and liquidate the business.

The Financials

Whenever I analyse a business I like to try and fundamentally understand exactly how it makes money.

This sounds obvious, but every business is unique and there are multiple different business models.

These all tend to generate cash in radically different ways.

Some are more desirable than others to a real-world owner in search of his next acquisition.

To understand Shinko Shoji, think of the business not as a creator of products, but as a capital lender that lends in the form of electronics.

To illustrate:

A manufacturer (Customer) needs computer chips.

Instead of buying them with cash today, they order them from Shinko.

Shinko uses its own cash to buy the chips from the factory (Supplier), stores them in a warehouse, ships them to the Customer, and waits 2-3 months to get paid.

This helps to explain the big influx of cash from the Renesas termination.

Prior to that, the company looked cash-poor because all its money was converted into chips sitting on shelves (Inventory) or bills waiting to be paid (Receivables).

When the massive Renesas contract ended, Shinko effectively recalled its loans.

They stopped buying new Renesas chips, sold what was on the shelves and collected the cash from customers.

The warehouse is now half-empty, but the bank account is overflowing.

The ¥31.7B cash inflow in FY2025 was the business converting its ‘loans’ back into cash.

The business is a financial fortress.

As of September 2025, over 70% of the total assets are liquid (Cash, Deposits, Securities, and Receivables).

It has no net debt.

It is effectively a bank vault with a smaller trading desk attached to it.

With this type of model you need to rely heavily on working capital.

To grow sales by ¥1, you must invest roughly ¥0.50 into inventory and receivables upfront.

This is why in FY22, despite being profitable, the business burned ¥11.6B in cash to fund growth.

This is just the normal operating cycle.

Under normal conditions, this business generates a thin margin (2-3%) on huge volumes.

The true cash flow only appears when the business stops growing and expanding its inventory.

This isn’t my favourite type of business-model but in a recession, this business generates cash as it sells down inventory.

It’s highly resilient to downturns.

The rapid liquidation of the Renesas inventory is a positive sign that even traditionally ‘difficult’ assets like inventory are very liquid here.

The problem, obviously, is that it requires a huge amount of cash to keep trundling along.

If we want to expand the top-line we need to suffer reduced FCF in the short-term.

The middleman business also suffers from a lack of pricing power. It’s pretty easy to get squeezed by both suppliers and customers.

All in all, we’re buying a massive pile of cash, that management is aggressively returning to shareholders, and getting a mediocre business for free.

Despite being valued as worthless by the market, interim operating profit is positive (¥516M) and it’s covering its own costs.

The risk of it actually burning through its assets and dying is pretty low, as things stand.

Why It’s Cheap

This is not a great business.

It’s not growing that much, and it has concentration risk, which was illustrated last year.

The margins are paper thin and rely on huge cash injections to move the top-line higher.

In FY25 the RoE was less than 1% (thanks to all the cash and reduced profits).

Management explicitly acknowledges this in the reports.

They are fully aware that the stock is trading far below its intrinsic value currently, and have an appetite to rectify that.

Ultimately, the market is refusing to rerate the stock price because it is sceptical about the 2028 plan to replace the lost revenues.

This is another common situation with Japanese companies holding lots of cash.

The Risks

At today’s price and with the current situation there is only really one main risk.

That is the risk of management burning through the cash (on costs and acquisitions) until the margin of safety has evaporated into thin air.

For me, conviction is built by specifically analysing the success of the Renesas revenue replacement.

For example, if the new business replaces top-line, but it’s all unprofitable, then this will turn it into a giant liability rather than an asset.

The plan is still in its infancy, so going forward this is where I’d spend most of my time and research.

It’s also worth noting that there is no particular concentration risk here.

No single owner holds enough voting power to take the company private at an absurdly low price.

There are also no specific poison-pill provisions to stop an activist taking a meaningful stake.

The Investment Case

The core idea is that the market has priced Shinko Shoji as a melting ice cube following the loss of its primary client (Renesas).

This ignores the fact that management has successfully monetized that loss into a massive cash pile and is actively deploying it to rebuild a more diversified, asset-rich business.

It also ignores the capital allocation skills and capital return track-record of the existing management team.

You are buying a dollar of liquid assets for 60 cents, with a profitable operating business attached for free.

You’re also getting a double digit yield (dividends and buybacks) while you hold the stock.

This is probably the clearest indication that the market has got its pricing wrong here.

It means that the operating business is being priced as a liability rather than any kind of profitable enterprise.

In reality, the operating business is actually cash-generative on a TTM basis.

This set up is open to all the usual catalysts.

First, the business has more than a good chance of returning to ‘normal’ over the next couple of years.

Next, there is ample cash and management track-record to pay out a special dividend or launch another aggressive buyback.

Finally, the ownership structure is conducive to some kind of activist involvement, although this is the least likely and would probably require something ‘friendly’ to succeed.

To complement all this, the management team are very conscious of the low stock price and are actively trying to rectify that for the benefit of existing shareholders.

This will also have the added benefit of helping them hit their RoE goal by reducing the cash-pile.

If you want to track the success of the ‘recovery’, I’d be inclined to monitor the following areas.

First, the profitability of the new business engine. The goal is to replace the lost revenue from the semi-conductor segment.

Management report by segment so this can be monitored fairly easily.

During the current year, sales here jumped 71% but profit dropped, due to the amortisation from the acquisition.

We want to see the profit for this segment stabilise and start growing again from here as a metric of success.

Next, we want to see good progress on the top-line and bottom-line figures going forward.

If revenues can make progress towards that ¥170B target, things should look good.

We also want to see net-income moving with it and FCF matching the typical pattern.

Again, the market is pricing things as if this has already failed miserably.

All we need is even a small glimmer of progress to disprove that assumption.

This, along with all the other things management is doing puts all the pressure on the upside and makes losing money on this stock, at this price, highly unlikely over the next 1-3 years.

To use a Walter Schloss analogy, the coiled sprint is maxed out to the downside and the only realistic direction from here is upwards.

My estimate of real-world TBV is ¥1746 per share, which is over 60% upside from current levels.

Get a 90% discount off Bloomberg’s No.1 competitor. Learn more here