A Japanese Cigar-Butt at 0.5x TBV

Also priced at just 3x FCF and 1.2x NCAV with increasing profitability and margins.

Get a 90% discount off Bloomberg’s No.1 competitor. Learn more here

The price of today’s stock suggests irreversible decline of its operating business for the foreseeable future.

It’s a classic cigar-butt that Walter Schloss would have been proud of.

Priced well below the price of its tangible assets which provides solid downside protection.

The annual reports however, show a stable operating business that has grown its revenues 5.5% and operating profits 28.3% YoY.

Right now, there is a disconnect between what is actually happening within the business and what the market is pricing in.

If the market is wrong, there is almost 80% upside to the tangible book value alone.

Let’s take a look…

The Valuation

Nikkato Corporation (5367.T) is a Japanese business, based in Osaka, and originally founded in 1913.

Let’s start with the key ratios for this business.

NCAV Ratio = 1.2

TBV Ratio = 0.55

EV/5Y FCF Ratio = 3.5

P/5Y FCF Ratio = 11

EV/FCF Ratio = 3

P/FCF Ratio = 9.5

The reported FCF figures appear to be solid and representative of what I could take out of the business if I owned the whole thing.

In 2021 the FCF was around ¥460M, and last year (FY 25) it was ¥780M. The 5Y average figure is ¥680M.

In other words, profitability is growing over time and continues to grow. The FCF yield at today’s price is 9-10%.

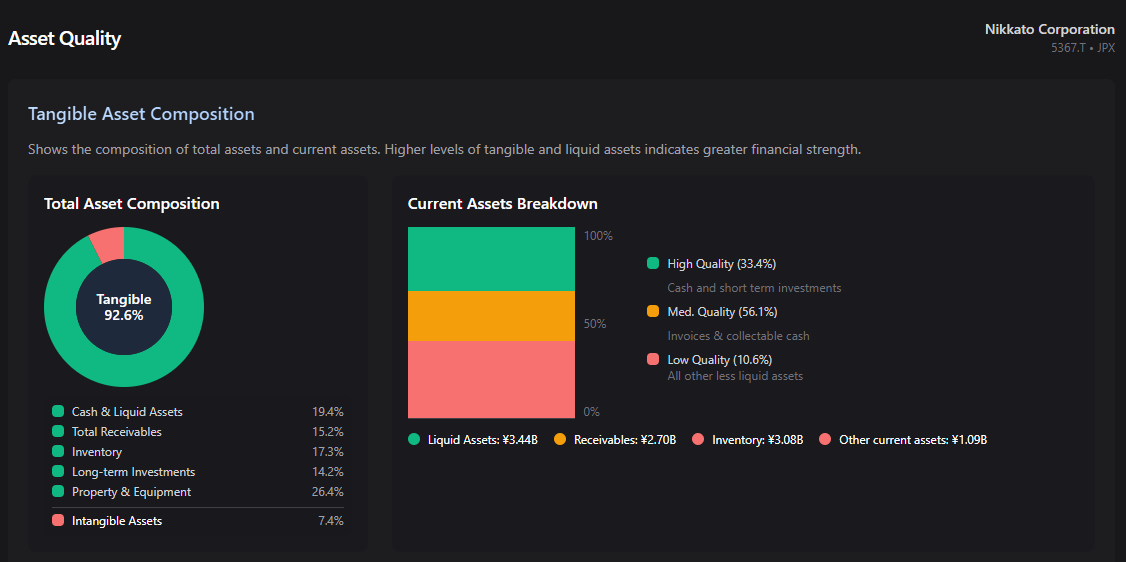

The tangible assets are also high-quality and easily converted into cash.

As you can see above, cash and liquid assets are around 20% of the asset base. This is supplemented by marketable securities, held in long-term investments.

When we add invoices, liquid assets are almost 50% of the total base.

Every penny of cash is unrestricted and available to both the operating business and the owner.

One interesting find is that the business owns the land where its main factory is located.

It seems to have been bought back in the 60’s.

I don’t like to get too carried away trying to calculate the value of land in Japan, but my research suggests this land is worth ¥2.5B rather than the ¥1B book value.

This is another layer to the margin of safety on today’s market cap of ¥7.43B.

If we count the land at book value, and ignore the decades of value accretion, the TBV is currently around ¥13.5B.

Because of the highly liquid nature of the assets, it also prices this business very close to its NCAV (but it’s not quite a net-net).

When buying a business the first thing to do is calculate the actual costs of acquiring it (obviously).

For me, I use the enterprise value above the market cap.

My logic is that I want to figure out all debts I’m going to be on the hook for, and then deduct this from the cash and very liquid assets I’d also inherit.

Then I can figure out if the earnings are powerful enough to generate a decent ROI in a relatively short period of time.

Obviously, for stocks I need to also include the cost of the shares in this calculation.

The calculation I use is as follows:

Market Cap (¥7.43B) + Total debts, inc all debt-like obligations (¥728M) - All liquid assets (¥5.8B).

Here, the business holds around ¥2B in marketable securities, under ‘non-current’ assets.

Because these can be converted into cash almost instantly, I include them.

Using this calculation the EV is around ¥2.3B.

This compares really nicely to the 5Y average FCF of ¥680M and last year’s figure of ¥780M.

In fact, it looks way too cheap, given how robust the operating business is.

Finally, we also need to consider the fact that we are minority shareholders in this situation.

I account for this by calculating the total shareholder yield over the last 5 years.

This lets me see whether holding the stock generates a positive return or an erosion of value.

One thing I like about this business is that they introduced a SBC programme in 2024, but used FCF to buy the shares rather than ‘issuing’ them.

We factor in the dividends paid, and the buybacks conducted along with any issuance or SBC activity.

The 5Y average yield is +3.1%, while the yield last year was 3.7%.

In other words, we get paid something to hold this stock while we wait for a catalyst.

In my view, this operating business is definitely not worthless, which gives us a solid foundation for a re-rating.

The Business

Nikkato operates in two distinct segments: ceramics and engineering.

When I think of ‘ceramics’ images of posh people sipping tea from pretty cups or eating their dinner off fancy plates springs to mind.

Or maybe someone making a vase in some studio.

Nikkato creates nothing like this.

Instead, their ceramics are more specialised in nature. For example, one of their products is something called ‘YTZ Balls’.

They’re used to pulverise and crush raw materials when making things like paints or pigments.

They also make something known as laboratory porcelain, which is used to make things like heat-resistant dishes or crucibles.

Apparently, these products are quite important to the process of creating electronic parts and components.

The engineering side focuses on things like heating equipment (electric furnaces, IT components and semi-conductors), and temperature measuring instruments.

In other words, they build very focused products for a very particular set of industries (mostly electrical components).

Ceramics generates 73.5% of revenues while the engineering side makes up the other 26.5%.

54% of the ceramics products and 21% of the engineering products are sold into the electrical components industry.

They do serve other industries, to a lesser degree, such as chemical, kiln-producers, car-makers and heavy machinery manufacturers.

90% of all sales are generated in Japan, but some products (like the TYZ balls) are sold globally.

Nikkato was impacted by COVID and the ensuing inflation spike, but the biggest challenge recently has been a cyclical dip in the electronics industry.

This caused ceramics revenue to fall by 8%, as demand for smartphones and PCs dropped in the 2024 financial year.

The engineering side did grow by 6% during that time, which acted as a kind of a ‘buffer’.

While the business is priced for permanent decline, the recent reports seem to show that the business has turned a corner.

This is where the 5.5% growth in revenues and 28% growth in operating profit comes in.

Meanwhile FCF is up 99% YoY and OCF is up 113% YoY.

This was mainly driven by a return of demand in the ceramics sector.

The Financials

When analysing the business through its financials, an interesting story emerges.

First, the cash-engine is mainly driven by OCF. This regularly exceeds net-income which shows a powerful ability for the business to make money.

Over the last 5 years, the business hasn’t failed to generate positive FCF.

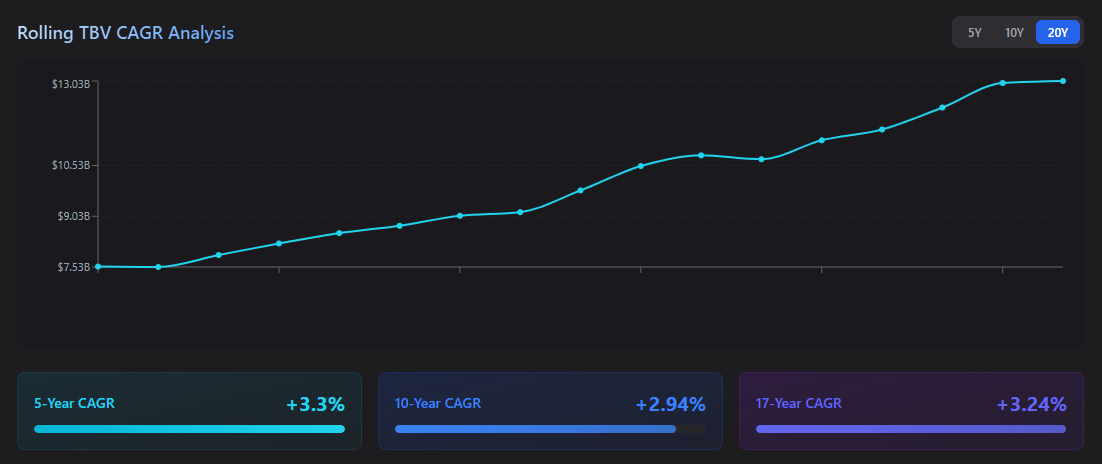

The balance sheet is a fortress of liquidity, and TBV has been growing over time, although it flattened out over the last couple of years.

The reason this is interesting is that it seems far removed from an operating business in terminal decline.

The income statement shows us that revenues are stable but cyclical. There isn’t really any growth, but there are a few interesting insights we can glean here.

First, the business has pricing power.

In FY23, when inflation was raging all around, the company increased its revenue by almost 8%, simply by raising its prices.

I’ve owned many businesses over the years, and can tell you from experience, that pricing power is something to be treasured.

Next, the two segments (ceramics and engineering) seem to complement each other nicely.

Over the last five years, whenever one has dipped, the other has grown to support it.

There are a few downsides hidden away in the numbers.

First, the fixed costs base seems high. When revenues fall, this can have a big impact on profits.

For example, in FY25 revenues dropped 1.6% but operating profit collapsed over 30%.

This was caused because the fixed costs were spread over fewer units sold, which killed margins.

The other thing I don’t like is something typical of a lot of Japanese stocks, which is the cash hoarding.

This creates a fortress of liquidity but it’s not great for compounding wealth. Unlocking this cash is obviously important to us as minority owners.

The business also generates a decent chunk of revenue from dividends. These come from the stocks it owns.

This income can be as much as ¥75M per year, although I have already included this in the FCF figure.

What I like about this is that the dividend income covers the debt-interest almost every year.

The debts are tiny, but it’s nice to have a buffer (that doesn’t burn cash) in case the operating business struggles.

The income statement seems to inflate depreciation way above what actual capex costs are.

This is a good thing (over multiple years) because it indicates to me that the cash available to owners is actually much higher than the ‘accounts’ suggest.

Why It’s Cheap

The stock price is up 24% in the last year, but it’s nowhere near what it should be for a business like Nikkato.

This lag is all down to the market’s perception of the business and its management team.

Essentially, the price is so low because the market is sceptical about the company’s ability to generate ongoing value via its operating business.

The cash-hoarding creates poor efficiency metrics which make the business appear lacklustre.

In other words, the management team has access to a financial fortress but doesn’t have the competence to use it efficiently in a sustained manner.

Governance reforms are happening in Japan.

One of the ‘measures’ is to encourage or even make it some kind of rule that each business must maintain a stock price above book value.

If a business has a PB Ratio below one, then action is required to fix it.

Nikkato management explicitly mentions this in the reports and have created a plan to deal with it.

Any sign that management is improving this situation is the key to a re-rating (more on this below).

The Risks

The reports contain plenty of information about risks that the business faces.

These include all the usual things like cyclicality, geopolitics and regulatory compliance.

It also includes a few notes on supplier concentration and the threat of no-one actually needing ceramic products anymore.

But none of these concern me too much, given how long its been operating successfully and how specialised the business is.

There doesn’t appear to be any concentration risk either.

In total, insiders seem to control around 36% of the voting power, while the free-float is around 60%.

They do have a ‘poison-pill’ mechanism to deter a hostile takeover, but the main concern for someone like me is an involuntary delisting at a low price.

This doesn’t appear to be a high risk here.

How to Build Conviction

To build confidence in a position here I’d focus first on that downside protection. Double check the assets and figure out the true value of the land.

This will be key to not losing money.

Next, I’d dig into the feasibility of the plan to get the stock price above book value. The plan basically involves increasing revenues to ¥13B and increasing margins to 15%.

Watch for progress there as a sign they’re genuinely improving the value creation power of the business (rather than decline).

The Investment Case

The business isn’t going to die. The current price offers almost guaranteed downside risk.

This is even more true when we factor in the hidden value of the land.

As we’ve already mentioned, the current price implies long-term decline but the operating business shows resilience and growth.

This has the hallmarks of an asymmetric set-up, where current price is dislocated from business reality.

Management acknowledges the low stock price (which is actually rare for Japanese cigar-butts to do).

They also revealed a plan called ‘connect 30’ which aims to address this issue.

They set two core targets for the business to achieve by 2030:

First, generate a 15% operating margin (FY25 was 6.3% and the last interim was 7.7%).

Second, expand revenues to ¥13B ( FY25 was ¥10.08B and TTM is ¥10.47B).

They have also decided to try and invest their cash for growth and change their culture to be more innovative, rather than overly-conservative.

The data so far suggests that they are succeeding in their quest for a more efficient business.

Of course, they are still only half way there in terms of margin, but it is creeping higher.

I also think there is a good potential for a special dividend or stock buyback programme.

This is because management has stated they plan to use the cash to add value.

Right now, buying stock at today’s price is probably one of the best-return investments they can make.

It’s also much easier and less hassle than trying to turn into a high-growth enterprise.

If I was the CEO, looking for an easy life, I’d simply announce a massive stock buy back programme and execute until the stock was priced fairly.

I do also believe a buyout or takeover is plausible.

Nothing hostile or ‘activist’ but the ownership structure contains plenty of related parties that may be interested in controlling the part of the supply chain that Nikkato operates.

An announcement of some ‘deal’ wouldn’t be too surprising.

All in all, I think there are many routes to a re-rating and this looks even more likely given the fact management are actively focused on it.

One way or another a re-rating seems likely over the next 2-4 years.

As previously mentioned the upside to TBV alone is over 80%, which is the target of the measures management is implementing.

This provides a target of ¥1137 per share (assuming TBV doesn’t continue to increase).

Get a 90% discount off Bloomberg’s No.1 competitor. Learn more here