Cheap Stock or Deep-Value Mirage?

When the lens of a private owner deters an investment into a perfectly healthy cash-cow.

Deep-value investing follows a simple-sounding premise:

We (try to) buy businesses at prices far below what they are really worth to any rational, real-world owner.

Sometimes this is a pretty simple equation.

But, other times, things get complicated, which makes the decision making process difficult.

The main issue in these ‘tricky’ scenarios basically boils down to conviction.

In some cases, the opportunity looks like a no-brainer. You can see clearly how the business is worth far more than today’s price.

In other cases, a stock looks cheap, but there may be a lot of moving parts, which erode conviction, as each little part is uncovered.

Today’s stock looks cheap.

But, when I dug into the details I felt like Neo when he first met the Oracle, in the Matrix movie.

What really baked my noodle was the following conundrum:

This business has cash. Lots and lots of cash. And lots of consistent FCF to go with it. Yeah after year.

To remain operational, however, most of the cash must stay inside the business, so an owner cannot easily get it out.

If it was liquidated, the cash is available to owners, but the tangible asset value is much lower than today’s market cap.

So, if it continues operating, it looks really cheap but you can never get the cash, and it’s currently priced too high for a liquidation play.

After staring at it for days, I’m still not entirely sure whether it’s cheap or not (for me).

I decided to write it up for a couple of reasons:

Firstly, there will be readers in my audience who will agree this stock is cheap and remain unphased by my conundrum.

Secondly, I like to share a variety of different situations and set ups to illustrate the paradoxical complexity of this super-simple deep-value approach.

If you have a passion for deep-value, these types of situations exist to make us better investors.

Here are the headline ratios:

NCAV Ratio = 7

TBV Ratio = 4

EV/5Y FCF Ratio = 1

P/5Y FCF Ratio = 5

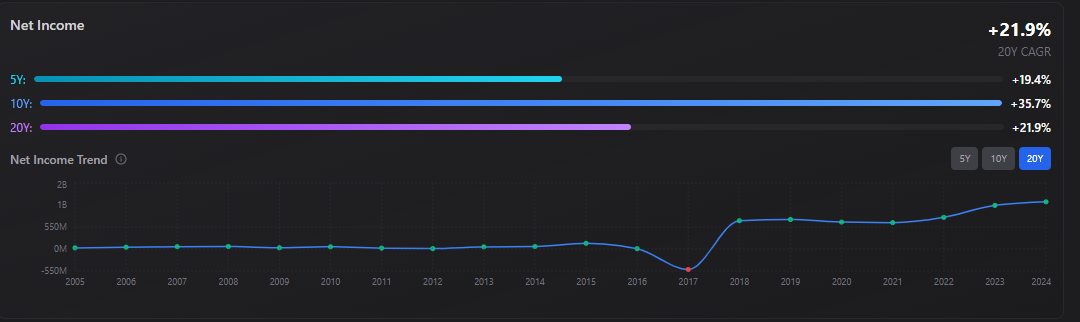

The earnings power of the business is impressive, with the vast majority of years (90%) throwing off positive FCF.

The business has also grown pretty impressively over the last few years.

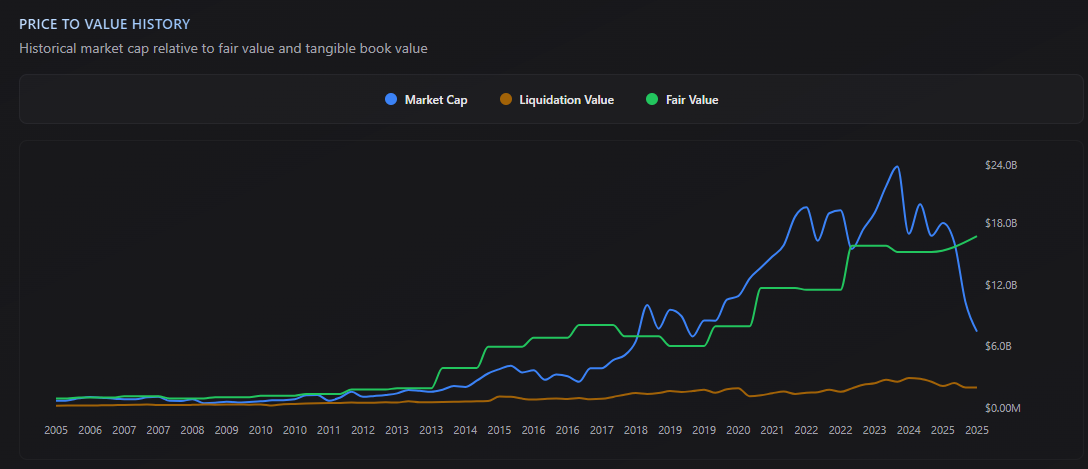

My view of this stock can be summed up by the visual above.

Generally, over the last decade, the market has priced this business, pretty consistently, above its ‘fair value’, as I calculate it.

(my calc explained here)

This year, the market has re-rated the stock severely. Pushing it well below the fair value level, and into the ‘cheap’ range.

Whenever I find situations like this, it always draws me in to look closer.

Let’s dig in…

The Business

Molina Healthcare (MOH) is a holding company that owns health-plans across the US.

Those health-plans provide medical cover to people enrolled in government programmes such as Medicaid, Medicare, and the AFC Marketplace exchanges.

In other words, each of the subsidiaries or ‘health-plans’ operates like an insurance company.

They receive premiums for each member and then distribute the pay-outs for medical care, and pocket the difference.

All the cash that the subsidiaries make stays there, and dividends are passed back up to Molina on a regular basis, but in a tightly controlled manner.

We’ll discuss this in more detail shortly.

The revenue model, works as follows:

Government agencies pay a fixed amount, per member, per month. This is determined by actuaries, and adjusted for things like age, health status, and other benefits.

Molina then uses that money to arrange and pay for each member’s care, depending on what (if anything) that member needs.

The premium fees are regularly ‘adjusted’ to make sure they adequately cover the real-world expenses of medical care for each member.

This is the main economic engine of the business.

Overall, around 79% of group revenues come from the Medicaid scheme, 14% from Medicare, and the rest from the ACA Marketplace.

The reports indicate that the focus on Medicaid is deliberate and that they consider themselves ‘specialists’ in delivering Medicaid care.

I’m not an expert on the US healthcare system, but it seems like this is due to Medicaid generating the best margins, overall.

Molina operates in 21 states, with Texas representing 14% of the Medicaid premium revenue in 2024.

Washington provided 13% and New York 11%.

This mix of states and composition is constantly changing, as various states switch away from Molina or expand their services.

This business has been specialising in Medicaid since 1980, so it would seem they know what they’re doing, to some degree.

The current CEO, Joseph Zubretsky, has led the business since 2017.

He has vast experience in the insurance industry and was even ranked as the 67th most influential person in US healthcare.

His expertise seems to be capital allocation and margin stability, with business growth.

In other words, this seems to be a solid business in capable hands.

Why It’s Cheap

Over the last two years, the stock price has fallen from a high of $400, down to today’s current low price of $137.

Two main things have soured sentiment on this stock.

First, the general negativity surrounding healthcare stocks in the US.

This has been driven by things like, higher costs, higher claims, lower margins and the current administrations desire to gut Medicare and Medicaid programmes.

Secondly, the business itself has suffered this year, with management cutting guidance a few times in the space of a few months.

For example, EPS fell from an actual figure of $21.45 to a guided figure of just $14.0 during 2025.

They also noted that 2026 EPS is likely to be broadly similar to the newly guided figure from 2025.

The business is clearly feeling those general headwinds.

(An interesting note here is that when EPS was last at that $14 figure (2022), the market priced the stock at around $330.)

All this has weighed on the stock price and brought it crashing back down to where we are today.

Another factor impacting the stock price has been general market moves.

For example, when rival companies issued their own profit warnings, Molina stock dropped in sympathy.

This happened a few times, throughout 2025.

Prior to this year, the stock price looked pretty solid and climbed in lockstep with the businesses growth in EPS.

This reiterates, for me, that Molina is a solid business being capably managed.

The Risks

Of course, Mr market doesn’t run around screaming and panicking for no reason.

For Molina specifically, there are a few risks to note.

First, the medical cost-trends are running higher. This is one of the main reasons margins are being squeezed right now.

Molina is paid a fixed monthly amount per member. If people use more care than expected, or drugs get pricier, the fixed payment may not cover it.

Over the last year, costs in Medicaid ran hotter because the average member needed more care and usage rose above the previous averages.

This was also impacted by new contracts (state of Virginia) that tend to begin more expensively and average out over time.

This is a structural risk, but also something management view as temporary.

For example, the standard response to situations like this is to push those actuaries to increase the premium fees to ensure real-world costs are covered.

Management frame all this as an ‘extraordinary’ situation, which they expect will normalise over the next 12-18 months.

The next risk is that of procuring contracts.

A few big state contracts drive a lot of revenue. If Molina loses a renewal, that state’s revenue can fall away.

In 2024, for example, California, Texas, Washington and New York each represented about 10%+ of Medicaid premium revenue.

Of course, this is another structural risk, but it’s also inherent in the entire business model that Molina have been specialising in since 1980.

Finally, we have political risks.

The US always seems like it’s fighting between providing free health care for all or providing it for no one.

These swings can seem unpredictable, which creates uncertainty, which the market detests.

Any policy changes or regulatory changes that negatively impact the Molina model, leave it exposed.

Aside, from these main risks, there are also more general risks that every other business faces.

The main problem with this investment idea, for me, popped up when I viewed the situation through the lens of a private owner.

As an owner, I want to suck cash out and spend it on the lifestyle of my dreams.

Molina has stacks of cash ($8.5b) across the group, and generates around $1b per year in FCF.

This looks inviting on a market cap of $7.5b.

The problem is that almost none of that cash is actually accessible to an owner.

Insurance companies are heavily regulated, and that regulation insists on almost all of the cash sitting inside the subsidiaries.

According to the latest filing, the subsidiaries can only send up to $500m to Molina during the year. Anything more has to be specifically approved by the regulator.

This means that the parent (Molina) can only extract cash when there is enough available above the regulatory limits.

Even when they have excess, extracting it depends on the mood of the regulator.

In other words, by the time you factor out the parent level debt, and the regulatory-required capital, there is hardly anything left for an owner to extract.

This, of course, would be available in a liquidation, but the current price is way above the liquidation value of the business to make that relevant.

Next, the FCF figure is for the group, not the parent.

In the real world, the owner wouldn’t have $1b of FCF available. It’s more like $500m per year.

This is from the net-dividends to the parent (Molina).

In other words, the amount of cash the subsidiaries send back up to the parent as dividends, net of the money they call back down to balance the books.

On a $7.5b market cap, this starts to look not-quite-so-cheap.

Another feature of the business model is their use of debt.

As the revenues and earnings grow, so does the debt. This is necessary because of how restricted all the cash is.

They use the debt to do things like stock buybacks.

This seems a bit weird, but in reality, there is no other option, if you want to actually extract value from this business, regularly.

Management are prudent and use this within strict covenants (which they have always adhered to), but I still find it a bit uncomfortable.

The truth is, that I’m just not confident enough to navigate the complicated (to me) world of insurance companies.

I still think Molina looks cheap, to those comfortable with insurance businesses.

But through my lens, as a rational, real-world owner, something doesn’t sit right with the current valuation and set-up.

I certainly wouldn’t buy the business privately, given all the restrictions on cash-extraction. And that makes me hesitate to buy the stock.

The risk here isn’t in anything external, but more that I can’t seem to generate enough conviction in the idea.

Conviction is critical when one of your stocks is sitting at all time lows.

The Investment Case

Molina Health is a solid business with good management.

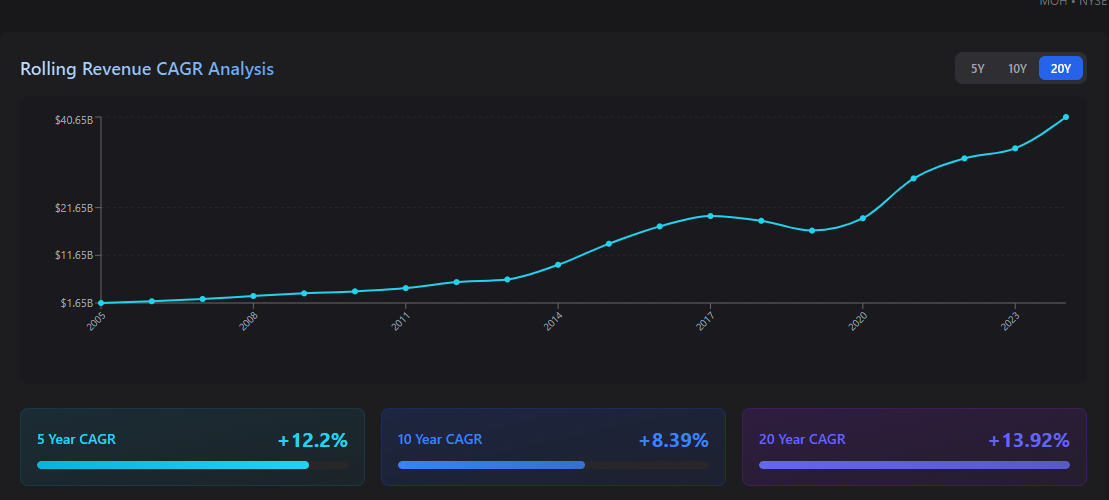

Check out the growth:

Revenues are up to over $40b while the market cap is just $7.5b. This alone makes the set up sound cheap imo.

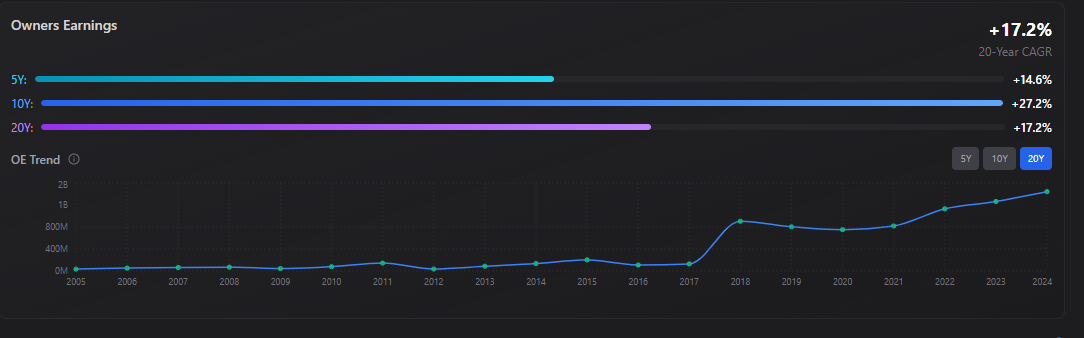

Group earnings are also growing across different metrics, although ‘owners earnings’ here isn’t quite what it seems (explained above).

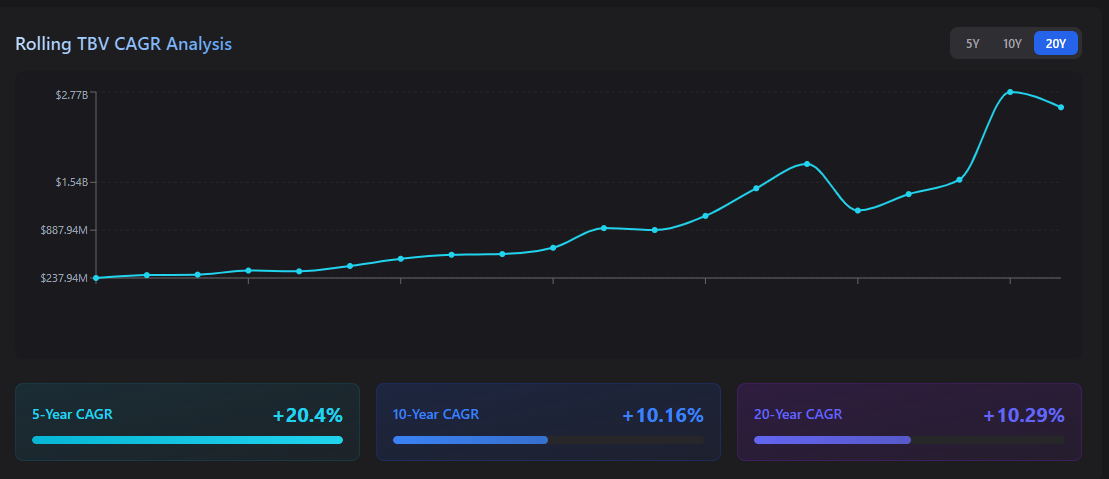

Even the tangible asset value of the business is growing nicely over a long period of time.

Management have stated that the issues they face may last throughout 2025, and start to stabilise in 2026.

They do not view these things as any kind of permanent decline and, instead, view them as temporary uncertainty they’re working to mitigate.

It’s highly likely, given their track record, that they successfully manage this period and get back to growth again in the next 2-4 years.

This is very likely to cause a significant rerating of the stock price, because it has always tracked business performance quite closely.

In fact, this recent sell off is the first time (I could find) that the price has dislocated from business performance to this kind of degree.

This all points to a temporary situation that mean-reversion will take care of, in due course.

I think this set-up would be of interest to anyone that doesn’t view the situation quite as conservatively as me.

It’s trading very low to group earnings, and the current P/E ratio is around half the long-term average.

This also indicates (to me) that the stock might be temporarily cheap.

They have recently started to ramp up buybacks as a way to take advantage of the lower stock price.

This, in itself, is a pretty glowing endorsement of the capital allocation skills of management.

All in all, it’s hard to imagine the business becoming permanently impaired, and the stock price remaining so far below the fair value of the business forever.

It’s on my watchlist for now and it would likely take a significant drop in price from here, to tempt me in (maybe as a liquidation play).

But, on the other hand, I will continue to follow it closely over the next couple of years.

Thanks for publishing this, and explaining the no-buy decision. I’m not confident regarding the insurance industry either, but it’s good to calibrate your thinking!